Refactoring needs direction.

Not all complexity deserves to die.

Complexity bad. Simple good. Most coding advice boils down to this. Nice soundbite but not terribly actionable.

In this post, we’ll examine what complexity actually is, identify its different types, and use this understanding to make better refactoring decisions.

What is complexity?

Complexity refers to the state of having many interconnected or interwoven parts, making something difficult to understand, analyse or predict. Or to put it more simply:

But complexity and WTFs/minute aren’t the same thing. We’ve all seen simple for loops that made us think “WTF?” and complex systems laid out so clearly that even without understanding every nuance, the intent was obvious. Good code minimizes WTF relative to its complexity. A well-structured complex system beats a confusing simple one every time.

Let’s look at the different types of complexity.

Essential vs. Accidental Complexity

Fred Brooks introduced us to a crucial distinction:

Essential complexity comes from the problem, not your code. Tax rules are complex; your implementation will be too. Product choices also add essential complexity: more features, more surface area. Managing essential complexity is a product job. And to be good at this, say “no” more often and build Vulcan features (for the many, not the few 🖖).

Accidental complexity is self-inflicted. Store usernames in a List and you invite duplicates, linear lookups, and defensive code that metastasizes. One “quick if” for a special-case leaks outward until the codebase normalizes the weirdness.

When we try and simplify code, our focus is accidental complexity. So, how can we measure this?

Finding the true complexity

Measuring WTF per minute is probably possible these days with a camera and some clever use of AI. However, there are some slightly easier alternatives:

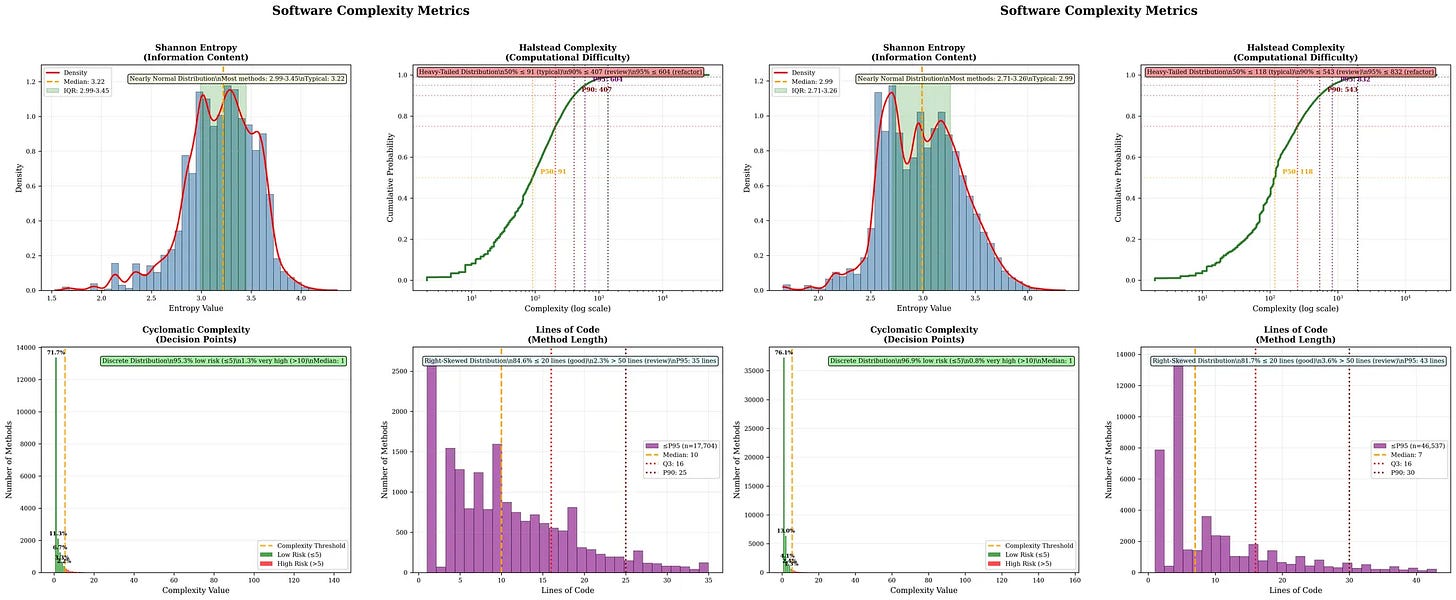

Lines of code. The more lines of code, the more complicated. Maybe?

Cyclomatic complexity. The more paths through the code, the more complicated it is. If I have a method with a complicated nested if/else structure, it’s more complicated than “straight-line” code.

Halstead complexity measures quantify software complexity by calculating the number of unique operators and operands and their total occurrences in the code. Programs with larger vocabularies and more operations require more effort to understand.

Entropy is a measure of the distribution of tokens (words). Higher entropy means more diverse elements; lower entropy measures more structure and repetition. Entropy, combined with the other metrics, can give an insight whether the code is predictably structured or chaotically diverse.

Metrics are blind to context. There can be simple code with high cyclomatic complexity (for example, a large switch statement—conceptually easy to understand but bad for this metric), and there can be short code with low complexity that’s hard to understand (imagine the fast inverse square root code without comments!).

In the image below1, there are two different codebases, and they have similar distribution curves. From this level you can’t distinguish essential vs. accidental. And that’s the point; these metrics alone won’t guide action.

These metrics can’t tell you which direction to refactor. They’re rudderless. Two developers with could refactor in opposite directions and both feel justified.

If you eradicate complexity of some code that’s never used or touched, then it’s busywork. It doesn’t improve your codebase and certainly doesn’t deliver any value for your customers. Instead, you want to find the areas of complexity that are causing the most pain.

How’d you find these bits? Well, often the complex code is the code that changes the most. The bash script below will help you find the code that’s changed the most, often a good target for refactoring.

N=5000

git log -n “$N” --name-only --pretty=format: | \\

grep ‘\\.cs$’ | \\

sort | uniq -c | sort -nr | head

Or you might want to ask the Support team? The complex code is where the most bugs lie, and your support team can tell you the areas of functionality that cause them the most grief.

But honestly? The easiest way to find the gnarliest code is just to ask people on your team. I’d bet good money that if you ask your team for the top three areas of complexity in the code base, they’d come back with similar lists.

Refactoring isn’t magic

Refactoring is the act of changing the structure of the source code without changing the functionality (else it’s a refuctoring - a refactoring that breaks things). The goal is often said to be reducing complexity. But let’s look at what’s actually happening with a few different refactoring’s:

Rename changes nothing about lines of code or cyclomatic complexity. The only type of complexity we can reduce is entropy by choosing a name that represents an existing concept.

Extract method has a different shape. The lines of code remain roughly the same, and the cyclomatic complexity is preserved; the logic is still there, just in a different place. The net effect is the same complexity, just spread across smaller, more digestible units.

Remove dead code is the most powerful slayer of complexity metrics—it reduces everything from lines of code to entropy. But equally, if some complicated code is just sitting around getting compiled and no-one sees it, then it’s not going to make life easier.

Refactoring moves complexity around. Extracting methods lowers local reading complexity but raises navigational complexity. Abstractions lower cyclomatic counts but raise conceptual overhead. But as you may have guessed already, choosing the refactoring based purely off metrics is a fool’s errand. How should you choose refactorings?

Without shared direction, refactorings become random walks. Dev A extracts methods for readability. Dev B inlines them for debuggability. Dev C adds abstractions to reduce duplication. Dev D removes them because ‘YAGNI.’ Six months later, the codebase hasn’t gotten simpler, it’s just thrashed. Different parts reflect different philosophies, and the inconsistency itself becomes the complexity.

As an example, I worked on a codebase and took a big, gnarly highly complicated class and split it into different pieces. But the end result was the same. Still many bugs, but now indirection making the code harder to reason about. Wrong trade-off! The real valuable refactoring (in this case) was to make the invariants explicit (replace primitives with objects) . This added more types (and more complexity) but it was the essential complexity needed to find the problems and ultimately reduce the accidental complexity.

Refactoring with purpose

Refactoring shouldn’t be about mindlessly driving metrics down. The antidote isn’t better metrics or more discipline, instead it’s having a team-wide sense of opinionated design that acts as a compass.

That opinionated design isn’t some grand architecture document. It’s agreeing as a team on conventions, patterns, and boundaries: How do we structure modules? How do we handle errors? Where do dependencies live? When everyone understands and follows the same principles, the codebase becomes predictable and navigable.

One hard-won lesson I’ve learned is to focus on being consistently OK, rather than inconsistently good! If you have an architecture that allows you to add features by following a pattern, it’s probably better than one where each feature is individually perfectly architected! Consistency creates leverage!

So the next time someone tells you to ‘reduce complexity,’ ask them: Which complexity? Where? For whom? And most importantly: Which direction are we all moving in? Without that shared direction, you’re not reducing complexity, you’re just churning it.

I vibe-coded a tool to calculate these stats for C# codebases. Roslyn makes this ludicrously simple (and then vibe-visualized with Python)